For de-escalation to truly be effective in any situation, merely knowing the skills and techniques from crisis intervention and negotiation training is not enough. To utilize these tools most effectively, we must grasp not only the situational context but also the intricate dynamics between us and those experiencing a crisis that influence the situation’s outcome.

Consider the analogy of a patient and their doctor: Is it sufficient for you to trust your doctor solely because they know a certain treatment works in specific cases? Or would you prefer a doctor who understands not only what treatment works but also why and how it works, and is prepared for instances when it might not work as expected? In essence, would you rather have your doctor treat just the symptoms or address the root cause of your ailment?

Similarly, just as a doctor who comprehends the underlying mechanisms of a treatment can better tailor their approach, perhaps by prescribing specific medications, dietary changes, or lifestyle adjustments, we are more likely to employ the most promising tools and techniques for sustainable de-escalation. A doctor informed about how a treatment works can also select adequate alternatives, for instance, when considering potential allergic reactions to medication. Likewise, understanding the desired outcome of an encounter and the most effective strategies to achieve it enhances our ability to de-escalate effectively.

Staller and team1 highlighted a similar concept in context of self-defence training and coaching. The team referred to Anderson’s2 adaptive control of thought (ACT) theory, which distinguishes between declarative and procedural knowledge, as means to navigate potentially violent situations. Declarative (or descriptive) knowledge represents the network of factual information and provides an understanding behind actions and principles (the ‘why’). With other words, it represents the theoretical understanding of concepts. In contrast, procedural knowledge involves knowing how to perform tasks and apply techniques in practice (the ‘how’). While it is evident that we need both to optimize outcomes, the distinction between declarative and procedural knowledge elucidates how they can operate independently:

The […] practitioner who does something (procedural) without knowing why (declarative), or the […] researcher, who knows why something works (declarative) but cannot apply that knowledge practically1.

Staller and team point out how self-defence situations are complex, dynamic, and rarely unfold in a linear manner. The resulting uncertainty also applies to other scenarios that require de-escalation (think crisis intervention or, truly, any inter-personal conflict) and which share the same characteristics: complexity, dynamicity, and non-linerity. Therefore, coping with it requires an understanding not only of the skills and techniques that help us deal with it but of its underlying causes, which lie within the situation, the other person, and ourselves.

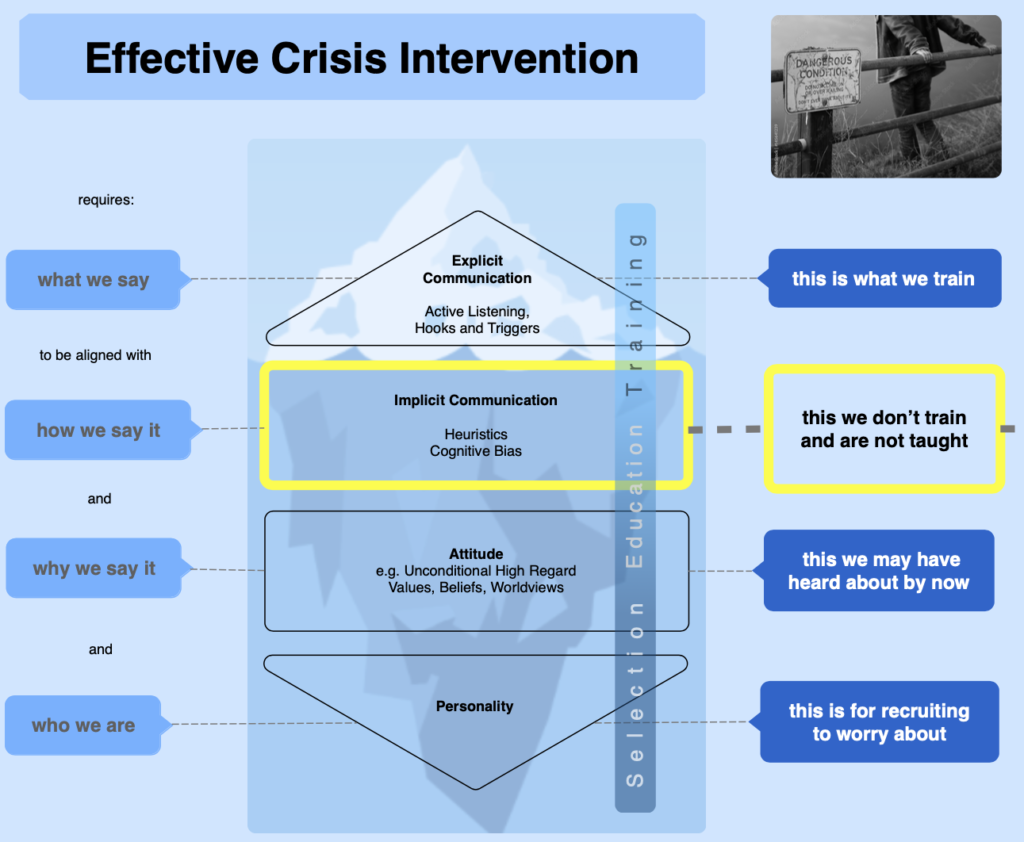

The iceberg graphic below represents the findings of our ongoing Heuristics in Crisis Intervention research project, embedded in an organizational context. The visible tip of the iceberg represents the aspects of which we are consciously aware and which shape most of our crisis intervention and de-escalation training: primarily procedural knowledge involving skills and techniques, such as active listening, identifying hooks and triggers, finding common ground, etc. However, as we delve deeper below the surface, we encounter the vast, submerged portion of the iceberg, symbolizing our diminishing understanding of the roles that implicit communication, attitudes, and personality play in our interactions. This depth reveals our shortcomings in declarative knowledge, highlighting the critical impact these underlying factors have on the success or failure of crisis intervention and de-escalation efforts. For the skills and techniques we practice to reach their maximum effectiveness, it’s essential that all segments of the iceberg—both visible above the water and hidden beneath—are in harmony. Achieving this alignment requires the acquisition of declarative knowledge that complements our procedural skills. This necessitates an educational approach that seamlessly integrates with current training methodologies, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the principles underlying our actions. Only through such a comprehensive educational and training approach can we ensure the full potential of our skills and techniques is realized, facilitating more effective outcomes in any application, from crisis intervention to everyday interactions.

The iceberg graphic offers a nuanced perspective on the intricate relationship between procedural and declarative knowledge, serving as a framework for enhancing our learning processes. At a holistic level, the tip of the iceberg represents procedural knowledge: the skills and actions we are directly aware of and utilize. In contrast, the vast, submerged section symbolizes declarative knowledge: the foundational understanding and principles that underpin our actions yet remain largely unseen and less consciously accessed.

Yet, this model also invites us to examine each segment of the iceberg individually, recognizing that both types of knowledge exist within every layer of our learning and practice. By dissecting these segments, we can delve into the specific declarative and procedural knowledge pertinent to each, enabling a more targeted exploration and integration of these knowledge forms. This approach not only broadens our comprehension of each domain but also facilitates a more effective synthesis of knowledge, enhancing our capabilities as learners and practitioners in any field, including crisis intervention and de-escalation.

References

- Staller, M., Körner, S., & Abraham, A. (2020). Beyond technique–The limits of books (and online videos) in developing self defense coaches’ professional judgement and decision making in the context of skill development for violent encounters. Acta Periodica Duellatorum, 8(1), 157-172. https://doi.org/10.36950/apd-2020-009 ↩︎

- Anderson, J. R., ‘Acquisition of cognitive skill’, Psychological Review 89/4 (1982), 369–406. http://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.89.4.369 ↩︎